Current Situation: A Neglected Women’s Disease

Osteoporosis remains significantly under-researched compared to cardiovascular disease (CVD), despite its profound impact on women’s health. While CVD, which primarily affects men, receives widespread attention, osteoporosis is often dismissed as an inevitable consequence of aging. Recent bibliometric analyses indicate that research on CVD outpaces osteoporosis studies by nearly 4:1, even though osteoporosis affects approximately 500 million people worldwide, including 21.2% of women and 6.3% of men over 50. 1

Although osteoporosis research funding at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has grown in recent years, exceeding $190 million annually, it remains disproportionately low compared to CVD research. In fiscal year 2023, the NIH allocated approximately $2.88 billion to cardiovascular research—more than 15 times the amount dedicated to osteoporosis. Moreover, the economic burden of CVD in the U.S. is staggering, with annual healthcare costs estimated at $555 billion and projected to surpass $1 trillion by 2035. This stark contrast in funding and prioritization highlights the need for greater investment in osteoporosis research to address its widespread and often overlooked impact. 2

The medical community’s neglect is mirrored in public awareness. 43% of women over 50 report fractures from minor falls, yet fewer than 30% receive post-fracture anti-osteoporosis therapies3. This systemic oversight reflects broader gender disparities in healthcare, where women’s conditions are often deprioritized.4

The lack of urgency in osteoporosis research and awareness campaigns highlights how women’s health is often deprioritized in medicine, despite osteoporosis affecting a significant portion of the population.

Osteoporosis Demands More Attention

Osteoporosis disproportionately affects women, yet women’s health education on the topic remains inadequate.5 According to recent statistics from the International Osteoporosis Foundation, worldwide, 1 in 3 women over the age of 50 years and 1 in 5 men will experience osteoporotic fractures in their lifetime.6

Postmenopausal women lose bone mass at 2–3% annually due to estrogen decline, yet the bone health education remains inadequate, particularly in low-income and rural communities7.

As global life expectancy continues to rise, osteoporosis is becoming an unavoidable crisis.8 The incidence of osteoporotic fractures is projected to rise significantly over the next few decades, with global estimates suggesting a 135% increase from 6.9 million to 16.2 million fractures annually by 2040.9 The lack of early intervention and effective preventive strategies will exacerbate the strain on healthcare systems, underscoring the need for policy reforms to enhance osteoporosis management and mitigate the impending burden.10,11

The consequences of osteoporosis extend far beyond weakened bones. Hip fractures are associated with 20-24% mortality within the first year, and survivors face a 5-year mortality risk 2.5 times higher than age-matched peers. Only 50% of patients regain pre-fracture mobility, while 40% lose independent walking ability and 60% require permanent assistive devices.7,12

Osteoporosis: Far Beyond Calcium and Aging

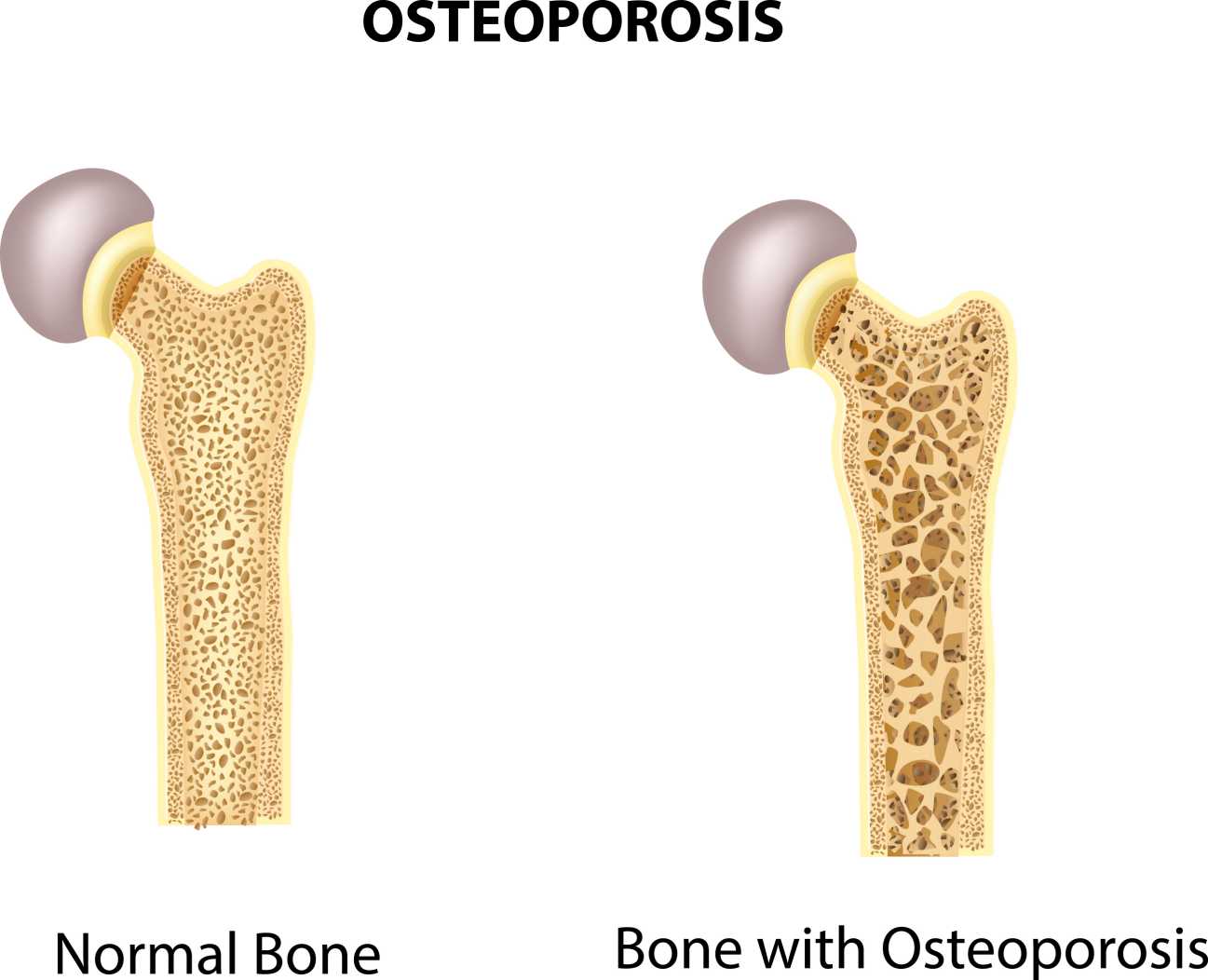

Calcium intake and aging are widely recognized factors in osteoporosis, but they do not fully explain the complexity of the disease. Recent research has identified additional risk factors that shape bone health throughout life.

Osteoporosis often begins long before old age. Poor childhood nutrition, low birth weight, and vitamin D deficiency can weaken bones early in life, increasing the likelihood of fractures decades later. These findings suggest that osteoporosis prevention should start early, rather than being addressed only in older adults.13,14

In addition to these early life factors, modern environmental and lifestyle elements significantly impact bone health. Chronic low-grade inflammation is recognized as a key driver of osteoporosis, with inflammatory cytokines accelerating bone resorption. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals like phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA) disrupts bone metabolism, making osteoporosis a consequence of both aging and environmental hazards. Furthermore, increasingly sedentary lifestyles contribute to bone loss due to a lack of weight-bearing exercise, which is essential for maintaining bone density. 15

Women’s Vulnerability to Osteoporosis

Women’s bodies are naturally more vulnerable to osteoporosis due to differences in bone structure. Women’s bones are 10–15% smaller and less dense than men’s, increasing fracture susceptibility. 16 Bone loss accelerates rapidly after menopause, leaving women with less reserve to compensate for declining bone density.17 Despite these biological differences, osteoporosis prevention is often approached with a one-size-fits-all strategy, failing to recognize that women require earlier intervention and tailored prevention methods. Lifelong attention to nutrition, physical activity, and medical screenings is essential to maintaining bone health. Strength training and weight-bearing exercises are particularly important, yet they are not widely promoted as osteoporosis prevention strategies.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding also have long-term effects on bone health. To support fetal development, the body diverts calcium from maternal bones, leading to temporary bone loss. While most women recover bone mass after pregnancy, those who experience multiple pregnancies in quick succession without adequate nutrition face an increased risk of developing osteoporosis later in life. The importance of bone health during pregnancy and postpartum is rarely discussed in routine medical care, leaving many women unaware of how reproductive factors can impact long-term skeletal integrity. 18

References:

1. Ganesan K, Jandu JS, Anastasopoulou C, et al. Secondary Osteoporosis. [Updated 2023 Mar 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470166/

2. https://www.statista.com/statistics/716599/cardiovascular-funding-by-the-national-institutes-for-health/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

4. Song Zhang. (2024). Research trends and hotspots on osteoporosis: a decade-long bibliometric and visualization analysis from 2014 to 2023

5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health; Snair M, editor. Overview of Research Gaps for Selected Conditions in Women’s Health Research at the National Institutes of Health: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2024 Aug 20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606165/ doi: 10.17226/27932

6. Pregnancy and lactation divert 5–10% of maternal calcium to fetal needs. While most women recover bone mass postpartum, those with multiple pregnancies and inadequate nutrition face 30% higher osteoporosis risk

7. International Osteoporosis Foundation (2024)

8. Tierney, N., McCarthy, B., & Davies, N. (2024). When is a fracture not just a fracture? Exploring emergency nurses' knowledge of osteoporosis in the West of Ireland. International emergency nursing, 75, 101482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2024.101482

9. Cui, L., Jackson, M., Wessler, Z., Gitlin, M., & Xia, W. (2021). Estimating the future clinical and economic benefits of improving osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment among women in China: a simulation projection model from 2020 to 2040. Archives of osteoporosis, 16(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-00958-x

10. Curtis EM, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Harvey NC. Osteoporosis in 2022: Care gaps to screening and personalised medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Sep;36(3):101754. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2022.101754. Epub 2022 Jun 9. PMID: 35691824; PMCID: PMC7614114.

11. Adami G, Fassio A, Gatti D, Viapiana O, Benini C, Danila MI, Saag KG, Rossini M. Osteoporosis in 10 years time: a glimpse into the future of osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022 Mar 20;14:1759720X221083541. doi: 10.1177/1759720X221083541. PMID: 35342458; PMCID: PMC8941690.

12. Rizkallah M, Bachour F, Khoury ME, Sebaaly A, Finianos B, Hage RE, Maalouf G. Comparison of morbidity and mortality of hip and vertebral fragility fractures: Which one has the highest burden? Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2020 Sep;6(3):146-150. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2020.07.002. Epub 2020 Aug 8. PMID: 33102809; PMCID: PMC7573502.

13. Winsloe, C., Earl, S., Dennison, E. M., Cooper, C., & Harvey, N. C. (2009). Early life factors in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Current osteoporosis reports, 7(4), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-009-0024-1

14. Javaid, M. K., & Cooper, C. (2002). Prenatal and childhood influences on osteoporosis. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism, 16(2), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1053/beem.2002.0199

15. Nurhasan Agung Prabowo. (2024) Environmental Factors and Osteoporosis

16. Office of the Surgeon General (US). Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004. 4, The Frequency of Bone Disease. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45515/

17. Arun S. Karlamangla. (2021). Chapter Fifteen - Hormones and bone loss across the menopause transition

18. Miyamoto, T., Miyakoshi, K., Sato, Y. et al. Changes in bone metabolic profile associated with pregnancy or lactation. Sci Rep 9, 6787 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43049-1

Post comments