West Nile Virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne virus that has garnered significant attention due to its potential to cause severe neurological diseases. First identified in the West Nile district of Uganda in 1937, the virus has since spread to various parts of the world, including North America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Australia, and Asia. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of West Nile Virus, its symptoms, transmission, and current status, including recent statistics.

What is West Nile Virus?

West Nile Virus is an RNA virus belonging to the genus Flavivirus, which also includes other notable viruses such as dengue fever, yellow fever, and Zika. The primary mode of transmission is through the bite of an infected mosquito, typically of the Culex species. These mosquitos acquire the virus by feeding on infected birds, which act as the primary reservoir for WNV. While humans and other mammals can become infected, they are considered "dead-end" hosts, meaning they do not contribute to the transmission cycle.

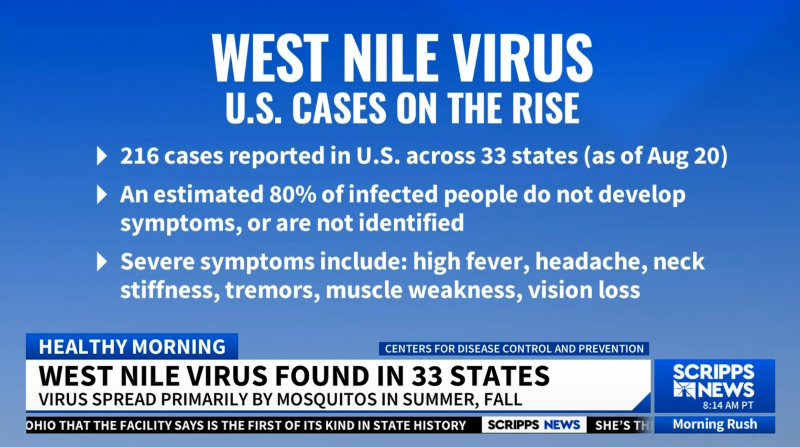

Most people infected with West Nile Virus do not exhibit symptoms. However, about 1 in 5 individuals may develop West Nile fever, characterized by flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, and pain behind the eyes. In rare cases, the virus can invade the central nervous system, leading to severe conditions like encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and meningitis (inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord). Symptoms of these severe infections include intense headaches, high fever, stiff neck, confusion, muscle weakness, tremors, seizures, paralysis, and even coma.

Transmission and Risk Factors

The primary vector for West Nile Virus is the mosquito, which becomes infected after biting an infected bird. The virus then multiplies within the mosquito and are transmittable to humans or other animals through subsequent bites. The incubation period, or the time between the mosquito bite and the onset of symptoms, typically ranges from two to six days but can extend up to 14 days.

While anyone can be bitten by a mosquito and potentially contracted by West Nile Virus, certain groups are at a higher risk of developing severe illness. These include individuals over the age of 60, organ transplant recipients, and those with underlying health conditions such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease. In very rare cases, the virus has been transmitted from a pregnant woman to the fetus, through human milk, blood transfusions, and organ transplants.

West Nile Virus is not directly contagious and fromperson to person. Therefore, the primary focus for prevention is on avoiding or reducing mosquito bites. This can be achieved through various measures such as using insect repellent, wearing long-sleeved clothing, and eliminating standing water where mosquitos breed.

Current Status and Management

Since its introduction to the United States in 1999, West Nile Virus has become the most common mosquito-transmitted virus in the country, with cases reported in 49 states. Over 51,000 symptomatic cases have been documented in the U.S. alone. Despite the widespread presence of the virus, the majority of infections are asymptomatic, and most people who develop symptoms recover completely. However, fatigue and muscle weakness can persist for weeks or even months in some cases.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of 2022, there were 2,695 reported cases of West Nile Virus in the United States, with 1,267 of these cases resulting in neuroinvasive disease. The states with the highest number of cases included California, Texas, and Arizona. The CDC also reported 191 deaths attributed to WNV in 2022, highlighting the ongoing public health challenge posed by this virus.

Diagnosis of West Nile Virus is typically based on a combination of clinical symptoms, history of mosquito exposure, and laboratory tests of blood or cerebrospinal fluid to detect antibodies or other markers of infection. Imaging studies like CT scans or MRIs may be used if there are signs of brain inflammation.

There are currently no specific antiviral treatments for West Nile Virus. Management of the infection primarily involves supportive care to relieve symptoms. For mild cases, this may include rest, fluids, and over-the-counter pain medications (non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs). Severe cases, particularly those involving neurological complications, may require hospitalization for more intensive care such as intravenous fluids, pain management, and measures to reduce edema and damages in the brain. In some instances, antiseizure medications, supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, corticosteroids, and tube feeding may be necessary.

Preventive measures remain the most effective strategy against West Nile Virus. These include avoiding outdoor activities during peak mosquito activity times (early morning and evening), using EPA-registered insect repellents, wearing protective clothing, and ensuring that living spaces are mosquito-proof by using screens and eliminating standing water.

In conclusion, while West Nile Virus poses a significant public health challenge, particularly for vulnerable populations, the majority of infections are mild and self-limiting. Ongoing efforts to educate the public about preventive measures and to monitor and control mosquito populations are crucial in reducing this viral infection and other mosquito-transmitted diseases such as malaria and viral encephalitis. As research continues, there is hope for the development of more effective treatments and possibly a vaccine in the future.

Post comments