Don't be surprised when you find that the once baggy jeans in your closet have turned into “skinny pants” - you're not alone. The global obesity problem is growing at a rapid pace, with one-eighth of the world's population already in the “obesity dilemma”!

Obesity is not just a matter of “one more circle around the waist”, but also a “reduction in the length of life”. In the face of obesity, weight management is particularly important. However, the process of weight loss is a “prolonged war”, requiring patience and scientific strategies. Many people who have successfully lost weight find that their weight bounces back quickly as if they have a memory. There is a scientific term for this phenomenon, called the “Yo-Yo Effect”. Many people lament: “I beat away the fat cells so hard, how always come back so fast?”

Recently, the international top academic journal Nature published the latest research reveals an interesting and headache phenomenon: obesity “molecular memory”. Even if the successful weight loss, fat cells are like a stubborn archivist, firmly remembered once obese state. The study found that in both human and mouse adipose tissue, obesity-related gene expression and epigenetic changes persisted after weight loss.

Adipocytes after weight loss surgery: How can researchers decipher their 'memory'?

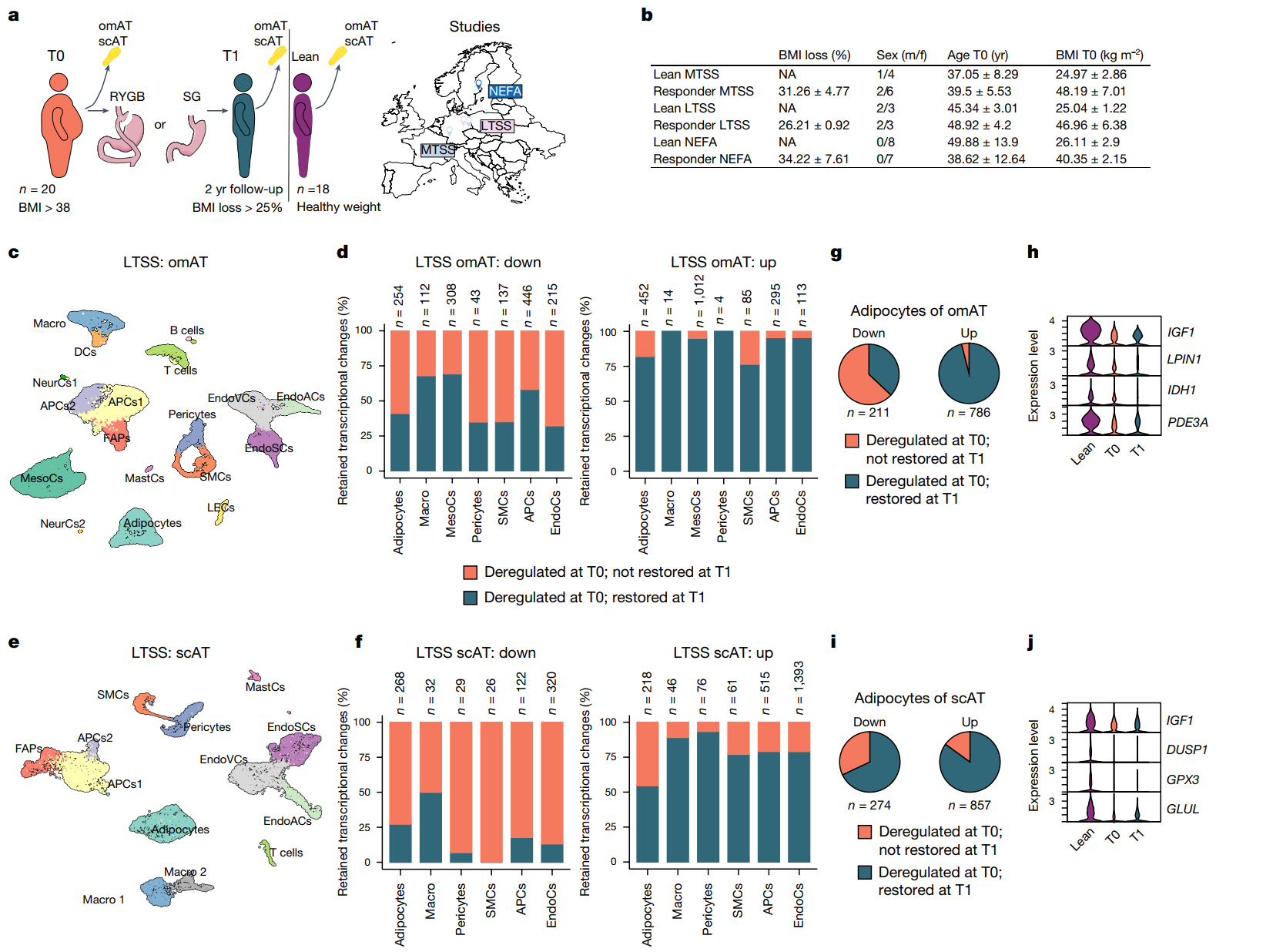

This study provides a comprehensive picture of the effects of bariatric surgery on fat cells by collecting adipose tissue samples from three independent clinical studies. These samples act as a “molecular diary” of obesity and weight loss, helping researchers to dig deeper into the “memory” of fat cells.

Two sets of samples from the MTSS and LTSS studies were taken from patients who underwent two-step bariatric surgery, a sleeve gastrectomy (T0) and a gastric bypass (T1). These samples included subcutaneous fat (scAT) and omental fat (omAT). To ensure the scientific validity of the samples, participants were required to have lost at least 25% of their body weight and have no history of diabetes as well as no use of hypoglycemic medications.

The third group of samples, from the NEFA study, focused on long-term changes in adipocytes before and after bariatric surgery. The study demonstrated how weight loss remodels the gene expression and metabolic properties of adipocytes by comparing adipose tissue before (T0) and two years after (T1) surgery. To enhance the reliability of the data, at the same time, the researchers also collected fat samples from a group of healthy controls for comparative analysis. Similarly, the participants were required to meet a body mass index (BMI) reduction of 25 percent or more and have no history of diabetes as well as no use of hypoglycemic medications.

These samples not only revealed transcriptional changes in adipocytes after weight loss surgery, but also provided a unique insight into whether weight loss can erase the “obesity memory”. Specifically, the researchers identified a total of 18 cell clusters, including adipocytes, adipose precursor cells, and macrophages, through single nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). Among them, the pro-inflammatory macrophages (LAMs) increased significantly in T0, which is the main culprit of obesity-induced chronic inflammation, disturbing the normal metabolic environment of adipose tissue; while in T1, the proportion of these pro-inflammatory cells decreased, but did not completely return to the healthy state, and chronic inflammation still exists.

At the same time, weight loss also had a significant impact on gene expression in adipocytes, but far from a “full recovery”; a large number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) remained after weight loss at T0. For example, genes associated with inflammation (e.g., TNF and IL6), although decreased after weight loss, remain at higher levels than in the healthy state, suggesting that chronic inflammation is not completely eliminated. In addition, metabolic genes related to fat storage and catabolism (e.g., FABP4 and PLIN1) were only partially restored, and the metabolic function of adipocytes was still affected. Fibrosis-related genes (e.g., COL1A1 and MMP9) remained at high expression levels after weight loss, which also suggests that fibrosis exists in adipose tissue.

Human adipose tissue (AT) retains cellular transcriptional changes after bariatric surgery (BaS) induced weight loss (WL)

These changes in genes and cell clusters suggest that “obesity memory” not only leaves deep traces at the transcriptional level, but also continues to affect adipose tissue health through chronic inflammation and metabolic disorders.

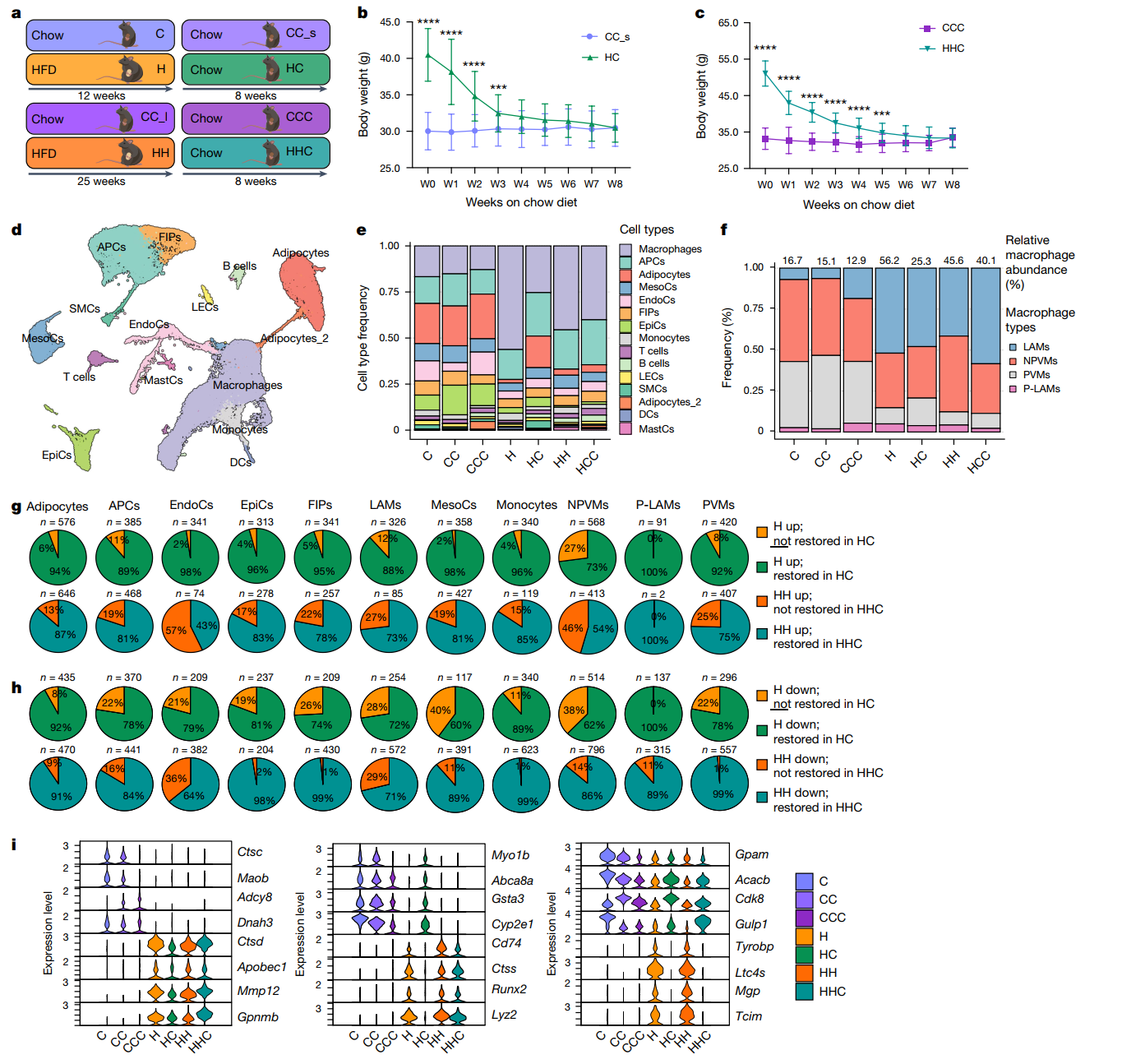

Is the “memory” of fat cells still at work after weight loss? Mouse experiments reveal the truth

The research team successfully fattened mice on a high-fat diet (HFD) while using a low-fat diet (LFD) as a control group. After 12-25 weeks of obesity, some of the mice achieved weight loss by switching their intake to a low-fat diet (WL).

The researchers examined a number of metabolic markers in the mice and found that even though the mice lost weight, some of the markers did not return to healthy levels:

Glucose metabolism was “impaired”: The obese mice had significantly reduced glucose tolerance, which manifested itself in elevated blood glucose and insulin resistance. Although there was some improvement after weight loss, the levels were not restored to healthy levels.

Fat distribution was “partially repaired”: fat mass was significantly reduced in the obese mice, but lean body mass remained largely stable, suggesting that the weight loss mainly consumed fat rather than muscle.

Liver “fat problem”: The livers of obese mice accumulated a large amount of fat (fatty liver), which improved after weight loss, but the liver lipid content was still higher than that of healthy mice.

In addition, pro-inflammatory macrophages in epithelial adipose tissue (epiAT) were significantly increased in obese mice, and inflammation-related genes (e.g., TNF and IL6) and fibrosis-related genes (e.g., COL1A1 and MMP9) were highly activated, which were difficult to recover from even after weight loss.

The results were further supported by epigenetic analysis:

Persistent openness” of chromatin structure: Obesity makes some inflammation- and metabolism-related gene regions in adipocytes more susceptible to activation. This chromatin openness was not completely closed even after weight loss.

Solidified memory” of histone modifications: Obesity-related histone modifications (e.g., H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) were persistently altered, affecting the on/off state of gene expression, especially in genes controlling inflammatory and metabolic signaling.

Transcriptional Changes in Adipose Tissue (epiAT) Persist After Weight Loss, Leading to Partial Remodeling

Interestingly, when mice that had successfully lost weight were re-exposed to a high-fat diet, the obesity memory of the adipocytes rapidly “awakened”, and these mice rebounded even faster than mice that had never lost weight. As mentioned above, inflammation in adipose tissue worsened, and the liver also showed fat accumulation and dysfunction. All of these metabolic abnormalities were highly correlated with epigenetic markers from the obese period, suggesting that obesity memories lay a deep “landmine” for weight regain.

In summary, weight loss is an uphill battle, but the bigger challenge is often to avoid weight regain. This study reveals the underlying cause of weight loss rebound from the molecular level - the “obesity memory” of fat cells. The team found that obesity not only expands the size of fat cells, but also leaves lasting traces at the genetic and epigenetic levels, so that these cells “can't forget the fat days” even after weight loss.

This study provides direct evidence that weight regain is not just a lifestyle issue, but that profound molecular and genetic mechanisms are behind it. This finding provides a new perspective on weight management: weight loss should not only focus on short-term weight loss, but also think about how to help fat cells “forget about fat” at the molecular level.

At the same time, the study also suggests that targeted epigenetic interventions (such as gene editing or drugs) may help fat cells get rid of the “shadow of the past”, to achieve “stable thin”, before we still have to fight against the “obesity memory”.

Source:Adipose tissue retains an epigenetic memory of obesity after weight loss | Nature

Post comments