An innovative injectable HIV drug, lenacapavir, has shown significant effectiveness in preventing infections, offering a promising new breakthrough in the fight against the virus.

An innovative injectable HIV drug, lenacapavir, has shown significant effectiveness in preventing infections. Despite substantial progress in preventing and treating new HIV infections over the past few decades, the virus still infects over a million people annually, and an effective vaccine remains elusive. This year, a drug that provides six months of protection with each injection has emerged as a potentially powerful protective measure. In June, a large efficacy trial among adolescent girls and young women in Africa reported that the injection reduced HIV infection rates to zero, achieving 100% effectiveness. Three months later, another similar trial across four continents confirmed this result, showing 99.9% effectiveness among a diverse group of individuals who have sex with men, dispelling previous doubts about the drug.

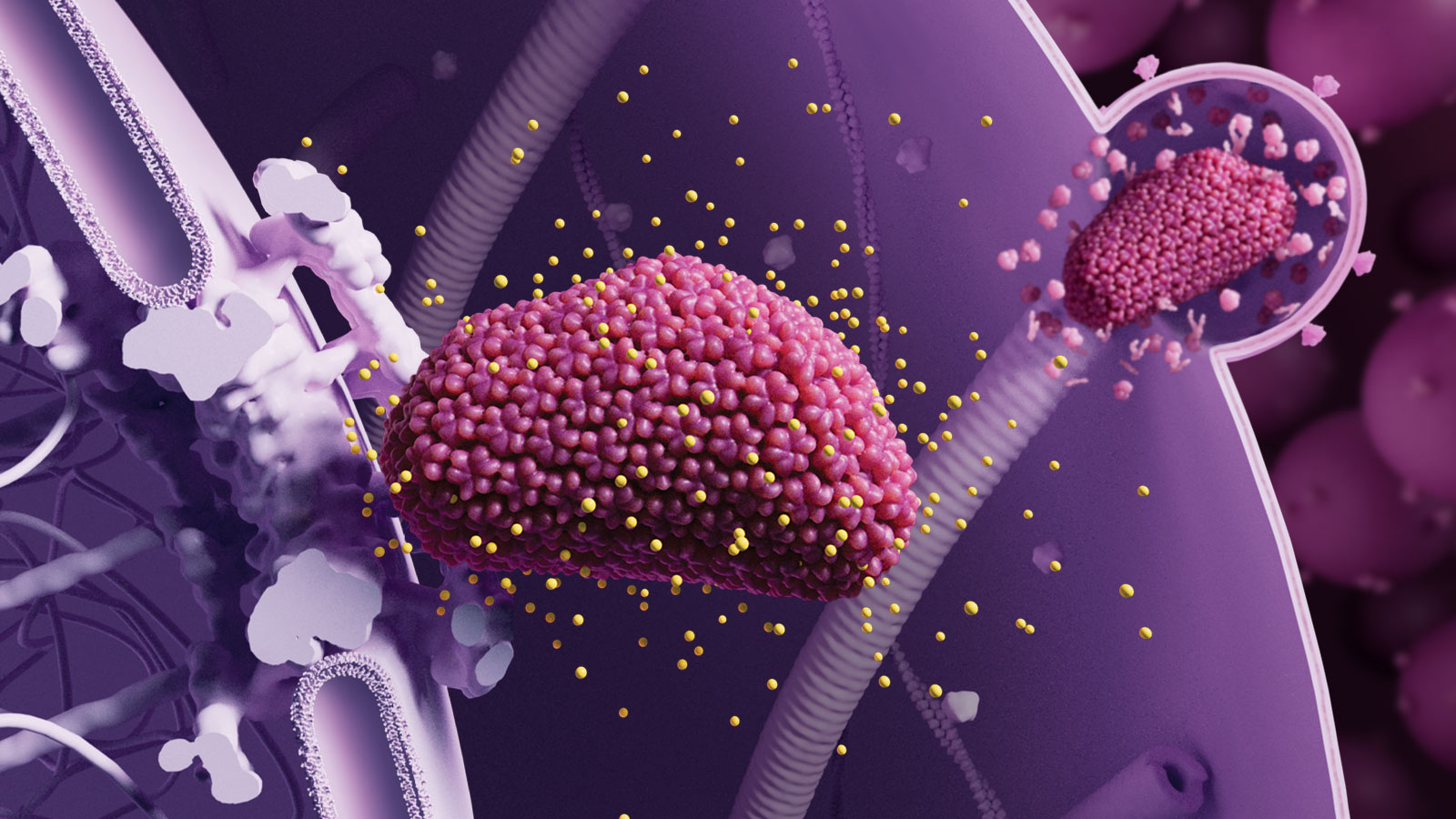

Many HIV/AIDS researchers hope that when used as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), lenacapavir can significantly reduce global infection rates. Linda Gail Bekker, an infectious disease expert at the University of Cape Town, stated, "If we can move in the right direction, this drug has enormous potential. We need to expand its application and actively promote it." She led one of the key efficacy trials conducted by the drug's manufacturer, Gilead Sciences. The drug's success as PrEP stems from a major breakthrough in basic research—a new understanding of the structure and function of the HIV capsid protein targeted by lenacapavir. Given that many other viruses also have capsid proteins that form protective layers around their genetic material, lenacapavir's success suggests that similar capsid inhibitors could combat other viral diseases.

HIV treatment has made significant progress over the years. In the early stages, HIV infection meant severe wasting, a severely compromised immune system leading to rampant infections, and early death. In 1996, researchers discovered that highly effective "cocktail therapy" could fully suppress HIV, delaying the progression of AIDS—a breakthrough named the breakthrough of the year by Science magazine. Current antiretroviral drugs are more advanced, allowing millions of patients to live normal lives with a chronic, manageable condition. Individuals who receive viral suppression treatment are also much less likely to infect others, leading Science magazine to name "treatment as prevention" the breakthrough of the year in 2011. As more people worldwide gained access to these drugs, new global infections dropped from 2.1 million in 2011 to 1.3 million last year.

However, it took years for poorer countries to gradually gain access to generic versions of these drugs. In many African countries, young girls and women only took these drugs intermittently due to stigma and interpersonal dynamics. In 2021, a PrEP drug called cabotegravir was introduced, requiring injections only every two months. Nevertheless, high costs and lack of public interest limited its widespread use. Research progress had stalled, leaving the world far from the UNAIDS targets of reducing new HIV infections to below 370,000 by 2025 and further to 200,000 by 2030. But lenacapavir broke the deadlock. In June, it caused a sensation in the PrEP field, with a double-blind study involving over 5,000 cisgender women and adolescent girls in South Africa and Uganda reporting zero infections among those who received the injection. In September, a second lenacapavir PrEP trial reported only two infections among over 2,000 cisgender men, transgender men and women, and non-binary individuals who have sex with men across South America, Asia, Africa, and the U.S.

Jeanne Marrazzo, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, stated that while lenacapavir PrEP is powerful, it cannot replace a vaccine. Marrazzo is optimistic that the drug can help significantly reduce HIV incidence in the most challenging regions. But a vaccine should be something that can be administered to everyone, not just high-risk groups; it should cost only a few dollars and provide years of protection with just a few shots. "If we truly want to eradicate HIV, we must continue to seek an intervention that creates lasting personal immunity." While injectable lenacapavir may not be enough to achieve the UNAIDS targets, it has the potential to protect millions from infection. This progress is an important addition to a series of significant biomedical breakthroughs, gradually transforming HIV/AIDS from a socially disruptive disease into a rare condition as these medical advances reach those most in need.

Source: Science

Post comments