by Sharon Reynolds

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is suddenly everywhere. From ChatGPT to automated customer service "representatives,” the ability of computers to perform increasingly complicated tasks is transforming society.

AI is also rapidly making its way into health care. One area where it’s being widely tested is in screening for cancer, to help interpret imaging-related tests like mammography for breast cancer and, increasingly, colonoscopy for colorectal cancer. But is it ready to assume a leading role?

According to a pair of new studies, when it comes to screening for colorectal cancer, that answer appears to be: Not yet.

One of the studies was the largest ever clinical trial to evaluate whether AI-based technology called computer-aided detection (CAD) can improve colonoscopy. Use of CAD, the study showed, didn’t increase the rate of detection of advanced adenomas—the growths most likely to become cancer—by experienced doctors.

Incorporating CAD into the screening procedure did increase the overall number of adenomas detected, but the increase was driven by the detection of much smaller growths, those least likely to become cancer.

The value of finding and removing these smaller growths, also called polyps, remains controversial. But the researchers, led by Rodrigo Jover, M.D., Ph.D., of the Hospital General Universitario in Spain, wrote that removing them does pose small but real risks, such as damage to the colon.

Their study was published August 29 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

A different study in the same issue reported similar results from an analysis of 21 previous clinical trials that had tested the addition of CAD to standard colonoscopy. Overall, the addition of AI increased the rate of polyp detection, but again, this was driven by an increase in detection of small polyps, not larger, more threatening growths.

The AI-based CAD used in these studies was not as advanced as the AI used to power newer tools like ChatGPT, explained Asad Umar, D.V.M., Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who was not involved in the new studies.

The systems used in these trials “are still kind of primitive AI—they’re not like what we’ve seen in 2022, 2023,” Dr. Umar said. Once more leading-edge AI technologies become integrated into CAD systems, he continued, they could potentially have a role in improving screening for colorectal cancer.

“The next versions [of CAD] are likely to be way better,” he said.

Does AI boost the performance of experienced doctors?

During a colonoscopy, a long, thin tube with a high-definition camera on the end of it, called a colonoscope, is guided through the anus, into the rectum and throughout the colon. A doctor performing the procedure doesn’t work alone, explained Dennis Shung, M.D., Ph.D., from Yale University, who wrote an editorial that accompanied the new studies.

“If I’m pulling out the colonoscope during the procedure and the nurse in my endoscopy suite says, ‘I think I saw something,’ I would go back and look every time,” he said.

Over the last decade, AI-based computer systems have been designed to perform a similar role for gastroenterologists, doctors who perform colonoscopies.

These systems are based on software that, as the colonoscope snakes through the colon, scans the tissue lining it. The CAD software is “trained” on millions of images from colonoscopies, allowing it to potentially recognize concerning changes that might be missed by the human eye. If its algorithm detects tissue, such as a polyp, that it deems suspicious, it lights the area up on a computer screen and makes a sound to alert the colonoscopy team.

Studies of these systems to date have provided conflicting evidence about whether they improve endoscopists’ performance. And previous clinical trials haven’t been large enough to determine if they make a meaningful difference in detecting advanced adenomas.

Finding small, not larger, polyps

To fill this data gap, researchers in Spain launched the CADILLAC trial in 2021. Researchers from six major colonoscopy centers enrolled more than 3,000 people who had blood in their stool found by fecal immunochemical test (FIT). People who test positive on a FIT are advised to get a follow-up colonoscopy because they’re at increased risk of having advanced adenomas or colorectal cancer.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either a standard colonoscopy (the control group) or colonoscopy with CAD. A total of 64 endoscopists from the six centers participated in the study.

Overall, advanced adenomas or colorectal cancers were found in about 34% of participants in both groups.

These results differ from those of some earlier, smaller studies that found that adding CAD to the procedure increased the detection of advanced adenomas and colorectal cancers.

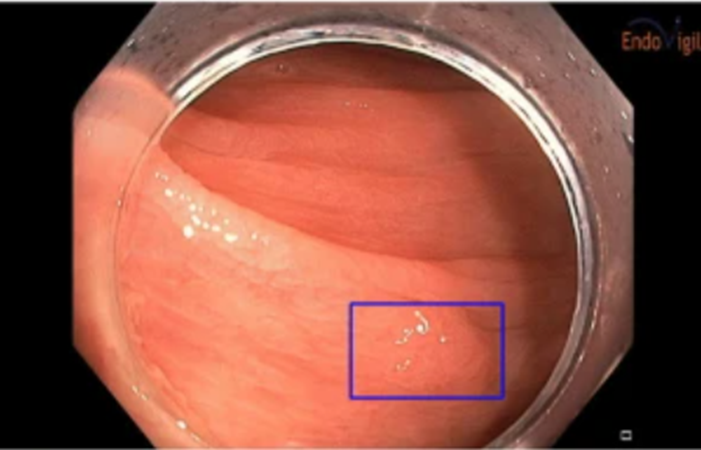

A "flat" polyp [purple rectangle] identified by computer-aided detection during a colonoscopy.

Credit: Scientific Reports. April 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10597-y. CC BY 4.0 DEED.

This difference may be, at least in part, because of the extensive experience of the participating endoscopists and the correspondingly high detection rate of advanced adenomas in the control group, the study team wrote.

“It is possible that in contexts of lower [adenoma detection rate] or in groups of endoscopists considered … “low detectors” there may be more effect of computer-aided detection systems,” they wrote.

Computer-aided detection did increase the number of small—less than 5 millimeters in diameter—polyps removed, even by experienced doctors.

Similar results were seen in the second study, carried out by a European research team, which analyzed the results of 21 previous randomized clinical trials testing CAD added to colonoscopy. The study, called a meta-analysis, included data on more than 18,000 people who had participated in the earlier trials.

As in the CADILLAC study, the meta-analysis showed that adding CAD increased the detection of small polyps—in this case, by more than 50%—but not of advanced adenomas.

Any polyp found on colonoscopy will be taken out during the procedure. So with increased detection of small polyps “we might be removing too many things that don’t necessarily need to be removed,” explained Dr. Umar. This is a phenomenon called overtreatment.

Any time a polyp is removed “there’s a risk of perforation and bleeding, because we’re taking a chunk out of the colon,” he continued. “It’s rare, but it does happen.”

A team member in the future?

That CAD didn’t improve detection of advanced adenomas in these studies was somewhat disappointing, because technologies that can speed up and streamline the workflow for screening colonoscopy need to be developed further, Dr. Umar explained.

Currently, the number of people who get a screening colonoscopy is far fewer than national guidelines recommend. “But we don’t have enough gastroenterologists to do as many colonoscopies as we need to do” he said. In some regions, such as some rural areas, the lack of trained specialists is already impacting the ability of people to get screened in a timely manner.

If AI-based systems could eventually speed up the process of colonoscopy, it could potentially help compensate for the workforce shortages in the field, Dr. Umar said.

In the current randomized trial, adding computer-aided detection didn’t slow the process, which is an important first step, he explained.

The technology may also eventually help with similar procedures, such as checking people with a condition called Barrett’s esophagus for early signs of esophageal cancer, Dr. Umar added.

Because precancerous areas in the esophagus tend to be flat, they are even harder to identify than growths in the colon and rectum. “But it’s the same problem everywhere [in the GI tract]: How do we identify lesions that are going to go on to become a cancer?” he said.

For now, AI systems may have a role to play in training much-needed new endoscopists, who will naturally miss more concerning polyps because they’re less experienced, Dr. Umar explained.

A truly game-changing advance would be a computer system that can provide some real-time certainty about whether polyps identified during colonoscopy are potentially dangerous, said Dr. Shung. Right now, tissue removed during the procedure needs to be sent to a pathologist for analysis, which can take days.

“On my wish list is an algorithm that could detect all the polyps and tell me if they’re cancerous [in real time]. … Then I’d be able to spend more time with the patient and counsel them about what they need to do [next],” Dr. Shung said.

Such systems won’t be in the clinic soon, but companies that produce colonoscopy equipment are already starting to build AI directly into their systems, added Dr. Shung.

“It’s [eventually] going to come directly with the endoscope—I think that’s going to be the future,” he said.

“People [tend to be] worried that AI will take their jobs,” Dr. Shung added. “But I think of AI as a team member, something complementary, that could [eventually free up time] to let humans take care of humans,” he said.

Post comments