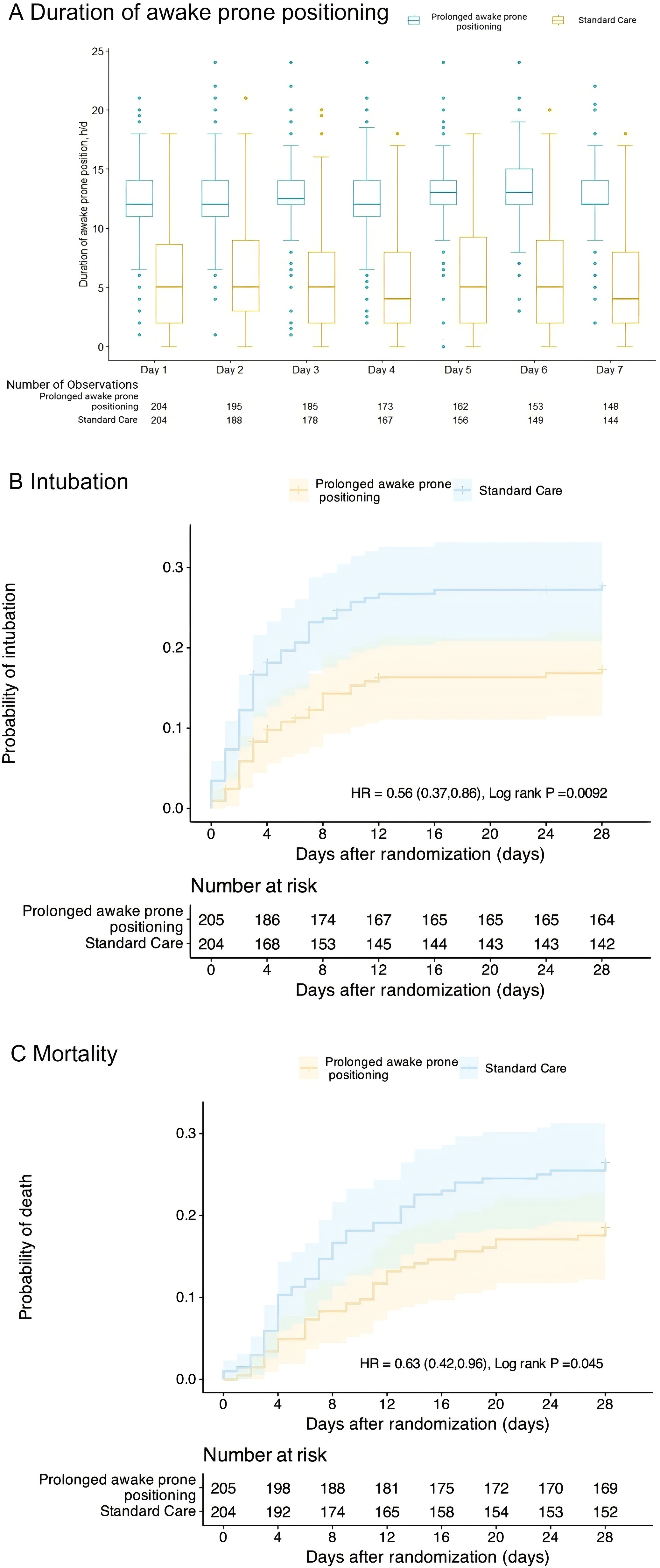

Duration of Awake Prone Positioning and Kaplan–Meier probabilities estimates in the intention-to-treat population. A The box plots display the median durations of prone positioning. The lines represent the median, the box edges represent the first and third quartiles, the whiskers represent the most extreme values up to 1.5 × IQR, and the dots represent the more extreme values. B Probability of endotracheal intubation*. The log-rank test demonstrated a significant between-group difference (P = 0.0092). *Patients who refused intubation after randomization were included as NOT being intubated. C Probability of death. The log-rank test demonstrated a significant between-group difference (P = 0.045)

Patients with COVID-19-related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF) often exhibit impaired oxygenation caused by pulmonary inflammation, microthrombosis, and ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch. Although mechanical ventilation can enhance oxygen delivery, it is associated with increased mortality rates and complications, such as pulmonary infections and barotrauma. During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, critical care resources were critically limited, especially in resource-constrained settings. Minimizing the need for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation became a critical healthcare priority to alleviate resource strain and improve patient outcomes. Previous studies have indicated that awake prone positioning can improve pulmonary V/Q ratios and reduce the need for intubation. However, high-quality evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on whether prolonged prone positioning can further optimize clinical outcomes remains insufficient.

Liu et al. conducted an open-label, multicenter RCT to assess the efficacy of prolonged awake prone positioning in reducing intubation rates and improving clinical outcomes compared to standard prone positioning. This trial was conducted in 12 hospitals across China, encompassing general wards, intensive care units (ICUs), and intermediate care units, during the pandemic's peak from January to April 2023. Eligible patients were adults aged 18–85 years with confirmed COVID-19-related AHRF (defined as SpO₂ ≤ 93% or PaO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 300 mmHg) who had not undergone endotracheal intubation. Exclusion criteria included inability to tolerate prone positioning due to conditions such as pregnancy, severe cardiac dysfunction, or impaired consciousness. A total of 409 patients were enrolled and randomized into two groups: the prolonged prone positioning group, with a daily target of ≥12 hours of prone positioning for seven consecutive days, and the standard care group, with <12 hours of daily prone positioning without mandatory duration requirements.

The study found that the intubation rate in the prolonged prone positioning group was significantly lower than in the standard care group (17% vs. 27%; RR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.42–0.90), with an absolute risk reduction of -10.75% (95% CI: -18.99% to -2.49%). Additionally, the mortality rate in the prolonged group was 19%, compared to 27% in the standard group (RR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.47–0.98), with an absolute risk reduction of -10.38% (95% CI: -18.39% to -2.36%). The mean number of days free from mechanical ventilation was longer in the prolonged group than in the standard group (22.2 days vs. 19.8 days; MD = 2.33 days, 95% CI: 0.06–4.61 days). Similarly, the mean hospital stay was 11.2 days in the prolonged group compared to 8.8 days in the standard group (MD = 2.36 days, 95% CI: 0.79–3.93 days).

Moreover, the incidence of adverse events was comparable between the two groups, with 8 cases (3%) in the prolonged group and 11 cases (4%) in the standard group, the most common being pressure sores. Subgroup analysis revealed that the benefits of prolonged prone positioning were more pronounced in patients under 60 years of age and in those receiving high-flow oxygen therapy or non-invasive ventilation.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that prolonged awake prone positioning significantly reduced the risk of disease progression in patients without notably increasing the incidence of adverse events. These findings not only enhance patient survival but also have the potential to alleviate the strain on medical resources, highlighting its strong clinical translational potential. The study introduced innovative strategies to optimize prolonged awake prone positioning, improve patient compliance, and extend its applicability to mild-to-moderate cases. These strategies were validated through a multicenter randomized controlled trial, confirming both their efficacy and safety. Compared to prior research, this study provides clearer operational guidelines for clinical practice and establishes a solid foundation for future investigations in this field.

However, due to the inherently operational nature of the intervention (awake prone positioning), the study was unable to achieve double-blinding of patients and caregivers. This open-label design may have introduced observer bias, particularly in the assessment of intubation criteria and patient compliance, where subjective judgment could influence outcomes. Although a standardized intubation protocol was implemented, decisions regarding intubation remained partially subjective. Additionally, 15% of patients in the standard care group also underwent prolonged prone positioning, exceeding 12 hours of daily prone positioning, potentially diluting the observed differences between the two groups.

These limitations underscore the need for further research into the management of prone positioning. Future studies should adopt more rigorous research designs and leverage technological innovations to explore optimal strategies, expand the applicability of prone positioning, elucidate its underlying physiological mechanisms, improve compliance management, and evaluate long-term outcomes. Such efforts could advance more precise and universally applicable clinical practices.

REFERENCES:Liu L, Sun Q, Zhao H, et al. Prolonged vs shorter awake prone positioning for COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory failure: a multicenter, randomised controlled trial[J]. Intensive Care Medicine, 2024, 50(8): 1298-1309.

Post comments