The Emergence of External Therapies in the Stone Age

• Bone needles with sharp tips, unearthed at the Upper Cave Man site and dated to 50 000–80 000 years ago, were not medical instruments, yet they show that piercing the skin was already technically possible.

• In the Neolithic period (c. 5000 BCE), finely polished bian stones with triangular or conical edges were found at the Cishan-culture site in Hebei; archaeologists regard them as the earliest prototypes of acupuncture tools.

Writing, Bian Stones, and the Formation of the Character for “Needle”

• Oracle-bone inscriptions record the practice of bleeding the arm by needling.

• During the Western Zhou dynasty, newly created bronze-inscription characters indicate that acupuncture tools were still chiefly made of bamboo, wood, bone, or horn.

• The Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shan Hai Jing) is the first Chinese text to link “stone needles” to specific regions and mineral resources.

Theoretical Foundations and the Nine-Needle System

• Silk manuscripts excavated in 1973 from the Mawangdui tombs—Moxibustion Classics of the Eleven Meridians of the Foot and Arm and Moxibustion Classics of the Yin–Yang Eleven Meridians—describe meridian pathways but mention only moxibustion, demonstrating that moxibustion preceded formal needling.

• The Lingshu section of The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon introduces the “nine needles” (round, sharp, filiform, etc.) and establishes concepts such as “obtaining qi” and “reinforcing–reducing,” thereby creating a theoretical model that links meridians, acupoints, and needling.

• The contemporaneous Classic of Difficult Issues (Nanjing) further specifies needle depth and retention time, transforming acupuncture from empirical craft into teachable technique.

Specialization of Medical Practice

• In 259 CE, Huangfu Mi compiled the Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, which catalogued 349 acupoints and their indications. It became East Asia’s first formal acupuncture textbook and influenced Korea and Japan for more than a millennium.

National Medical Education and Licensing Examinations

• The Sui dynasty established the Imperial Medical Office (Taiyi Shu). During the Tang dynasty this was expanded into a four-tier acupuncture curriculum: Doctor, Assistant, Technician, and Student. Candidates had to pass examinations based on The Yellow Emperor’s Acupuncture Canon and The Illustrated Classic of Acupoints.

• Sun Simiao’s Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces devotes Chapter 29 to acupuncture and moxibustion, presents the first colour illustrations of acupoints, and advocates the combined use of both methods—establishing the clinical model of “acupuncture and moxibustion complementarity.”

• In 753, the monk Jianzhen brought The Yellow Emperor’s Canon and The Systematic Classic to Japan, leading to the creation of an official acupuncture department within Japan’s Bureau of Medicine.

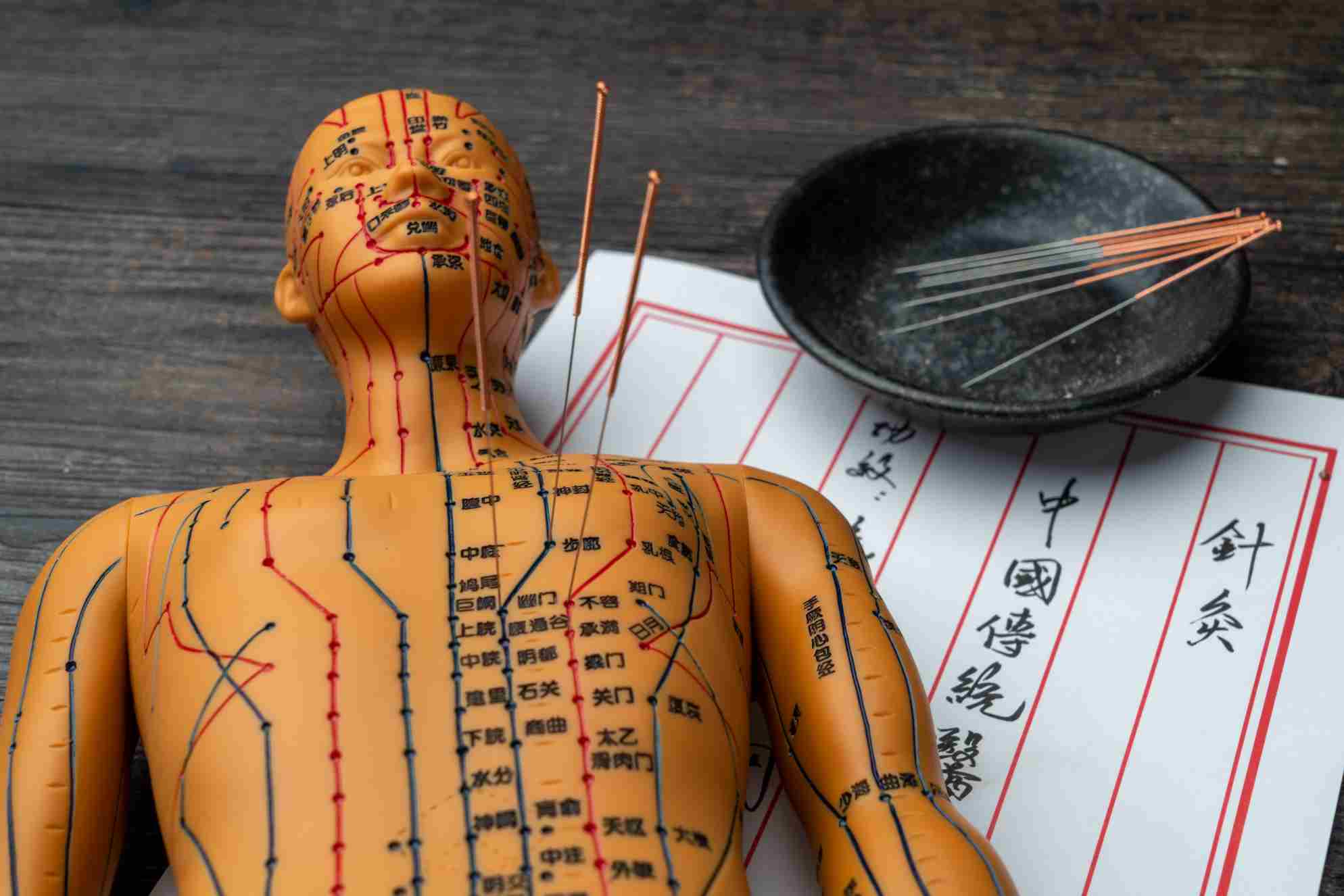

Bronze Models, Standardised Acupoints, and Diverging Schools

• In 1027, Wang Weiyi of the Northern Song dynasty cast two life-size “Bronze Men” engraved with 354 acupoints. Mercury inside the models would leak when a point was needled correctly, making them the world’s earliest medical teaching manikins for state examinations.

• The Illustrated Classic of Acupoints on the Bronze Man was carved on stone tablets in Kaifeng for public copying—effectively the first open-source release of acupoint data.

• Although the Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan dynasties (Liu Wansu, Zhang Congzheng, Li Dongyuan, Zhu Danxi) were chiefly known for internal medicine, each proposed differing interpretations of reinforcing–reducing needling techniques, fostering the diversification of acupuncture schools.

From Imperial Texts to Folk “Inner Landscape” Charts

• Yang Jizhou’s Great Compendium of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1601) synthesised more than 20 earlier sources, listed 359 points, and included 151 illustrations. It remains one of the most frequently cited classical texts worldwide.

• The Qing dynasty’s Golden Mirror of Medicine: Essential Rhymes of Needling and Moxibustion used rhymed verses to standardise techniques, facilitating memorisation by folk practitioners. Concurrently, methods such as “Divine Needling of Taiyi” and “Thunder-Fire Needling” emerged, expanding moxibustion with medicated sticks.

• In the seventeenth century, European missionaries introduced acupuncture to the West. Dutch and French Jesuits such as Willem ten Rhijne and Jacob de Bondt translated excerpts from The Great Compendium into Latin, stimulating debate in Paris and Vienna.

Suppression, Scientific Revival, and Global Legislation

• In 1822, the Daoguang Emperor ordered the permanent abolition of acupuncture from the Imperial Medical Academy, causing its official decline; nevertheless, it survived through folk transmission.

• During the 1930s–40s, Cheng Dan’an founded the China Acupuncture Research Society and published Chinese Acupuncture Therapy. For the first time, anatomical terms were used to describe acupoints, and practices such as alcohol disinfection and disposable needles were introduced.

• In 1951, the “Acupuncture Therapy Research Institute” (forerunner of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences) was established in Beijing, initiating systematic clinical and neurophysiological studies.

• In 1971, acupuncture anaesthesia for open-heart surgery appeared on the front page of The New York Times, sparking Western interest.

• In 1979, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed 43 indications for acupuncture; in 1997, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a consensus statement confirming acupuncture’s efficacy for post-operative dental pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and morning sickness—catalysts for legislation worldwide.

• In 2010, “Traditional Chinese Acupuncture” was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

• In 2021, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) released ISO 17218:2021, establishing specifications for single-use sterile acupuncture needles—marking the full industrial standardisation of this ancient practice.

Conclusion

From stone bian tools to sterile disposable filiform needles, and from “piercing with stone” to real-time fMRI imaging, the evolution of acupuncture is a documented journey connecting minute incisions with vast meridian networks and micro-level neuroscience. The discipline has preserved such classical concepts as “obtaining qi” and “reinforcing–reducing,” while continuously subjecting itself to the scrutiny of randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews. One silver needle, one smouldering moxa stick—traversing millennia—continues to demonstrate that techniques and theories may evolve, yet experience and evidence ultimately converge.

Post comments