In recent years, microplastics (MPs) have become a global environmental concern. These tiny plastic particles, which are less than 5 millimeters in size, are everywhere, from the depths of the ocean to the peaks of mountains. But their impact goes far beyond what meets the eye. A new study has found that MPs play a significant role in facilitating antibiotic resistance in bacteria, a discovery that has serious implications for public health.

MPs are generated from various sources, including the breakdown of larger plastics, industrial processes, and the use of microbeads in consumer products. Once released into the environment, they can easily find their way into water bodies, soil, and even the air we breathe. What makes MPs particularly concerning is their ability to act as carriers for bacteria and other harmful substances.

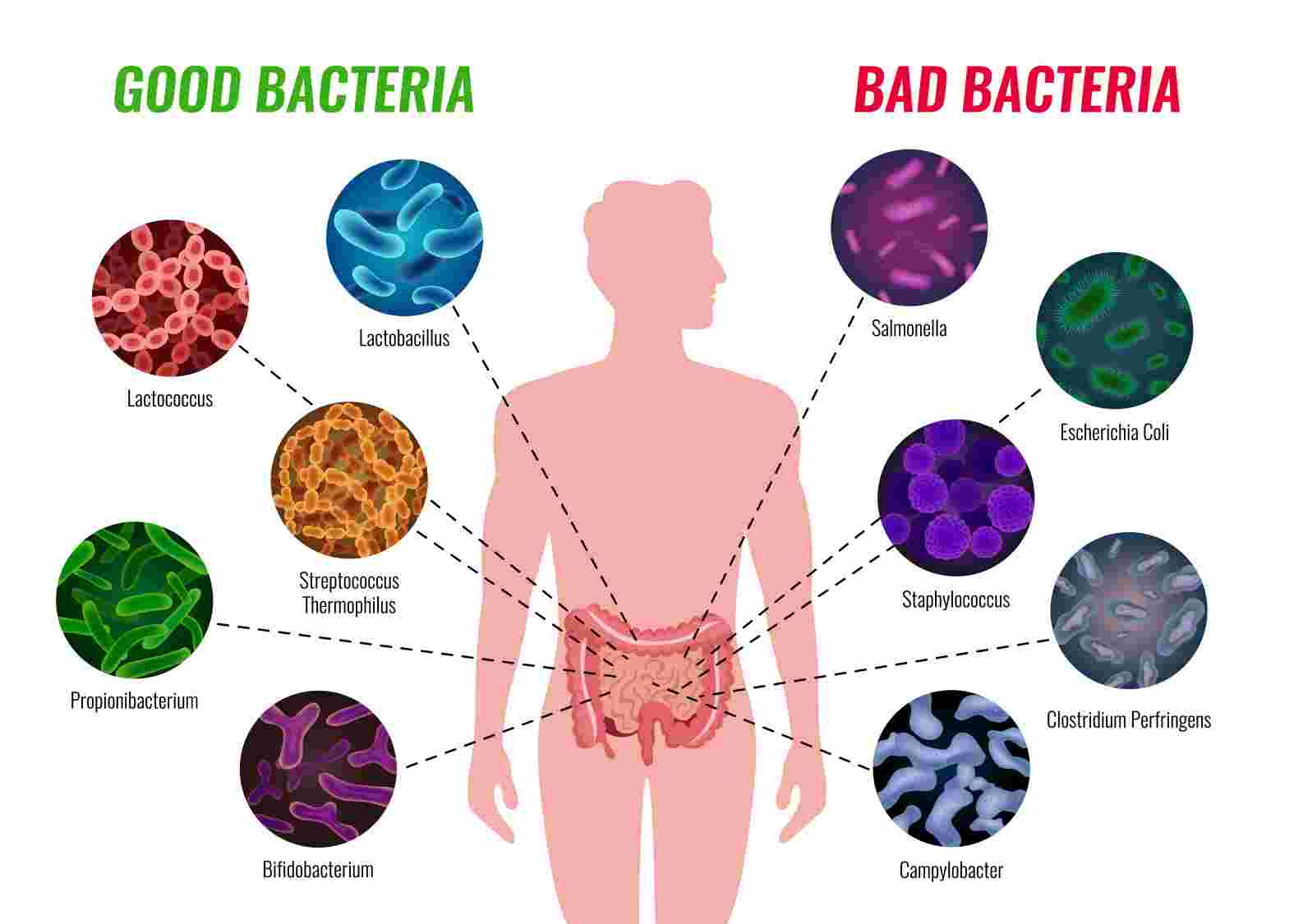

The study focused on Escherichia coli, a common bacterium found in the human gut and the environment. Researchers exposed E. coli to different types of MPs, such as polyethylene, polystyrene, and polypropylene, at various concentrations and sizes. They then tested the bacteria's resistance to a range of antibiotics, including ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and streptomycin.

The results were striking. Bacteria attached to MPs showed a significant increase in multidrug resistance compared to those grown without MPs. This means that the presence of MPs made it easier for the bacteria to develop resistance to multiple antibiotics simultaneously. Even when the MPs were removed, the bacteria that had been exposed to them formed stronger biofilms, which are communities of bacteria that are more resistant to antibiotics and difficult to treat.

One of the reasons MPs facilitate antibiotic resistance is their hydrophobic nature. This property allows MPs to adsorb chemical contaminants and genetic material containing antimicrobial-resistant genes (ARGs). When bacteria colonize the surface of MPs, they can easily exchange these ARGs through horizontal gene transfer, increasing their resistance to antibiotics.

Another factor is the surface area and composition of MPs. Larger MPs provide more space for bacteria to attach and form biofilms, while different plastic compositions can affect the rate of bacterial attachment and biofilm growth. For example, polystyrene MPs were found to have the most significant impact on resistance development, even though it is relatively more hydrophilic than other plastics tested. This suggests that there are complex interactions between MPs and bacteria that influence resistance.

The implications of these findings are far - reaching. In areas with poor waste management and inadequate wastewater treatment, the presence of MPs in the environment is likely to be high. This could lead to an increase in antibiotic - resistant bacteria, making it more difficult to treat infections in humans and animals. The problem is particularly acute in low - and middle - income countries, where access to clean water and proper healthcare is limited.

To address this issue, it is crucial to develop effective strategies to reduce the release of MPs into the environment. This includes improving waste management systems, reducing plastic consumption, and developing new technologies to remove MPs from water and soil. Additionally, more research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind MP - mediated antibiotic resistance and to find ways to prevent it.

In conclusion, microplastics are not just an environmental nuisance; they pose a serious threat to public health by facilitating antibiotic resistance. It is time for individuals, industries, and governments to take action to protect our environment and our future health.

References

Gross, N., Muhvich, J., Ching, C., Gomez, B., Horvath, E., Nahum, Y., & Zaman, M. H. (2025). Effects of microplastic concentration, composition, and size on Escherichia coli biofilm - associated antimicrobial resistance. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 10.1128/aem.02282 - 24.

Frias, J., & Nash, R. (2019). Microplastics: finding a consensus on the definition. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 138, 145 - 147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.022

Horton, A. A., Walton, A., Spurgeon, D. J., Lahive, E., & Svendsen, C. (2017). Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Science of the Total Environment, 586, 127 - 141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.190

Akdogan, Z., & Guven, B. (2019). Microplastics in the environment: a critical review of current understanding and identification of future research needs. Environmental Pollution, 254, 113011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113011

Martinez, J. L. (2009). Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environmental Pollution, 157(10), 2893 - 2902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2009.05.051

Wang, H., Xu, K., Wang, J., Feng, C., Chen, Y., Shi, J., et al. (2023). Microplastic biofilm: an important microniche that may accelerate the spread of antibiotic resistance genes via natural transformation. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 459, 132085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132085

Sathicq, M. B., Sabatino, R., Corno, G., & Di Cesare, A. (2021). Are microplastic particles a hotspot for the spread and the persistence of antibiotic resistance in aquatic systems? Environmental Pollution, 279, 116896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116896

Sun, Y., Cao, N., Duan, C., Wang, Q., Ding, C., & Wang, J. (2021). Selection of antibiotic resistance genes on biodegradable and non - biodegradable microplastics. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 409, 124979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124979

Ferronato, N., & Torretta, V. (2019). Waste mismanagement in developing countries: a review of global issues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16061060

Post comments