Penicillin allergy labels (PAL) are common in clinical practice, especially among patients in intensive care units (ICUs). Research indicates that approximately 15% of hospitalized patients and 6.8% of ICU patients are labeled as penicillin-allergic. However, many of these labels are not based on true allergic reactions, but rather on historical reports or misdiagnosed reactions. This mislabeling contributes to the inappropriate use of antibiotics, resulting in complications such as infection recurrence, prolonged hospital stays, increased readmission rates, and elevated healthcare costs. Traditional methods for diagnosing penicillin allergies, including skin tests and serological assays, often face limitations in ICU patients due to high rates of false negatives and false positives, complex procedures, and time-consuming processes. To overcome these challenges, the direct oral penicillin challenge (DOC) has emerged as a promising alternative for allergy assessment. DOC is not only simple and fast but also provides more reliable allergy evaluations in clinical settings. Although some studies have demonstrated the efficacy of DOC in non-ICU patients, its application and safety in ICU settings remain insufficiently explored.

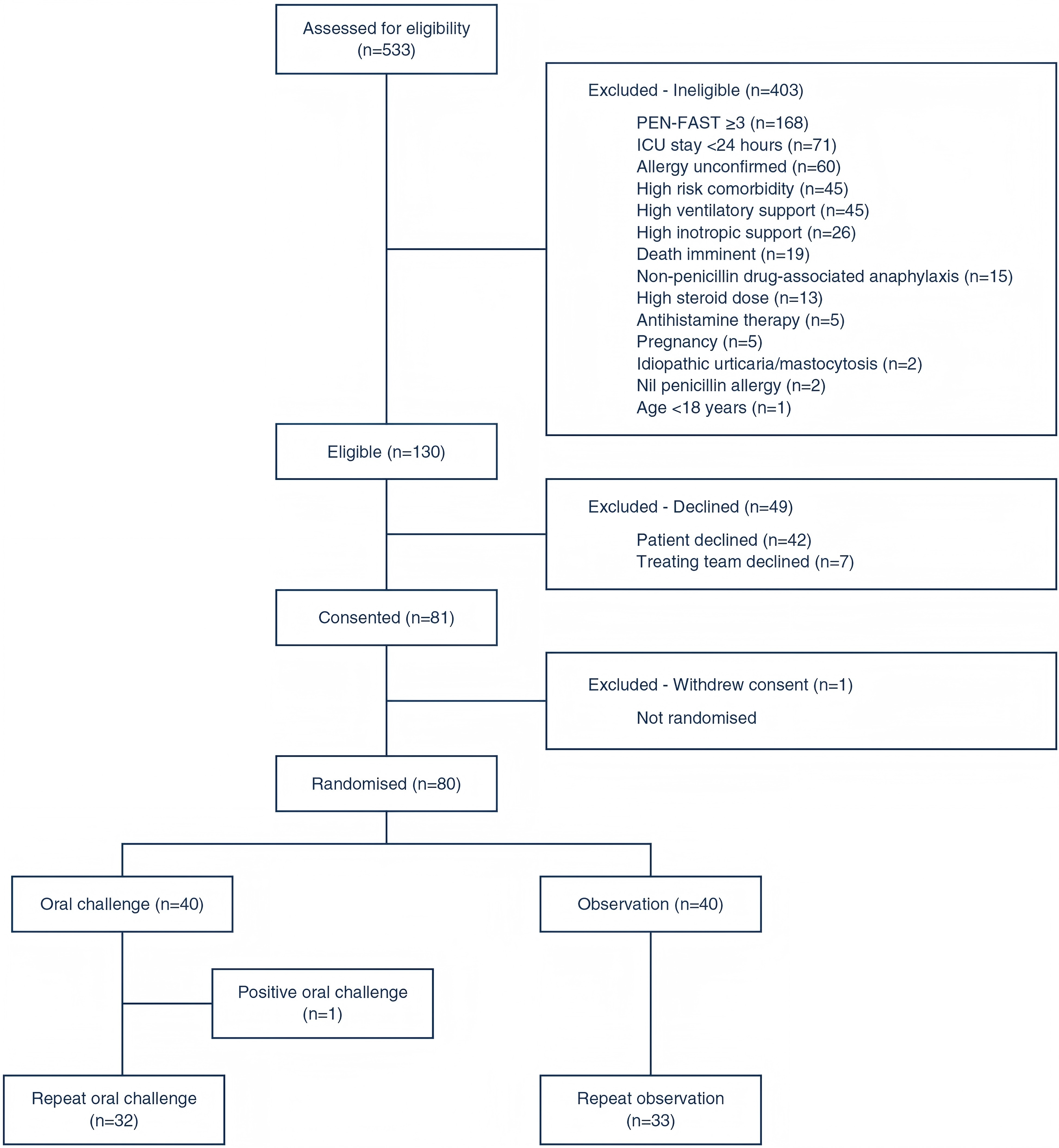

To evaluate the feasibility and safety of DOC, Rose et al. conducted a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial involving ICU patients with a penicillin allergy label. These patients were categorized as low-risk for penicillin allergy (PEN-FAST score < 3) using the PEN-FAST scoring tool. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group. Patients in the intervention group underwent a 250 mg oral penicillin challenge with agents such as amoxicillin or phenoxymethylpenicillin, followed by a 2-hour observation period to monitor for adverse reactions. If patients remained stable and the initial challenge was negative, a second challenge was scheduled once their condition further stabilized. Patients in the control group received only a 2-hour routine observation without the oral challenge.

A total of 533 patients were screened for eligibility, with 130 meeting the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 80 patients were successfully enrolled, yielding a recruitment rate of 61.5%, which met the feasibility standard. Notably, 80% of patients in the intervention group and 83% in the control group completed the study protocol, demonstrating that the oral challenge method was effectively implemented and well accepted in the ICU setting.

Regarding safety, only one patient in the intervention group (2.5%) experienced a mild allergic reaction, characterized by pruritic erythema, which fully resolved within one hour following antihistamine administration. No immune-mediated serious adverse events were reported, and all 32 patients in the repeat challenge group remained free from new allergic reactions, further confirming the method's safety for low-risk patients.

In terms of antibiotic use, 32% of patients in the intervention group received penicillin, compared to only 10% in the control group (OR=4.33, p=0.019). This finding suggests that, after removing the penicillin allergy label, patients were more likely to be prescribed penicillin, thereby optimizing antibiotic use.

Regarding hospital stay and mortality, no significant differences were observed between the intervention and control groups in terms of ICU length of stay, total hospital stay, or mortality rates, indicating that the oral challenge method did not significantly impact hospital stay or mortality.

The direct oral penicillin challenge method proposed in this study, combined with the PEN-FAST scoring tool, provides a fast, safe, and efficient approach for removing penicillin allergy labels in ICU patients. Compared to traditional skin tests and serological assays, this method offers significant advantages, including ease of use, rapid response, strong adaptability, and low cost. This study introduces an innovative allergy assessment strategy for clinical practice, which can improve antibiotic stewardship, reduce unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and ultimately enhance patient treatment outcomes and prognosis.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, and the study was conducted at only four hospitals, which may limit the generalizability of the findings due to regional and patient diversity. Future studies should include larger sample sizes and multi-center research across a broader range of hospitals and regions to validate the findings. Second, this study focused solely on patients with low-risk penicillin allergy labels, and the safety and efficacy of oral challenges in high-risk patients remain unexplored. Furthermore, although short-term follow-up was included, the long-term effects of the oral challenge, the potential for re-allergy, and the impact of long-term penicillin use were not fully assessed. Future research should incorporate extended follow-up periods to evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of the oral challenge.

REFERENCES:Rose M T, Holmes N E, Eastwood G M, et al. Oral challenge vs routine care to assess low-risk penicillin allergy in critically ill hospital patients (ORACLE): a pilot safety and feasibility randomised controlled trial[J]. Intensive Care Medicine, 2024: 1-9.

Post comments